i waited for you in the park.

when you arrived,

you held me,

and your cold nose pressed against my neck.

you nuzzled me,

and our skin quickly

adapted to one another;

mine cooled, or yours warmed

i’m not sure.

i was happy and

excited about what we might become.

the sun and an early spring day

marked the passage of time

and life moving forward.

these were early days—before

waiting became an annoyance,

before illness,

when i didn’t understand what

holding my breath truly meant.

the anticipation of test results slowed time,

and hours in the treatment chair

felt like lifetimes.

after my first seizure,

when the illness forced my world apart,

time shifted.

you found me

coming to the emergency room

to gather the pieces.

fresh from outdoors,

from the chill of an early

chicago spring day,

remembering this:

your cold nose

pressing into my neck,

i can still feel it as time slowed.

and why can’t these moments

be eternity?

when two bodies

seek a common temperature,

can’t this search last forever?

Tag: testicular cancer

The wind through an open door

At night, lying on my back, I stay awake and listen to the rattling of my lungs.

A wheeze, a strange resonating noise—like damp leaves—if mold had a sound, if abandoned rooms with winds spoke.

I insist I am okay.

I’ve always said, “I’m okay.”

From my youth, my father’s glare, to now, the groan of my lungs.

But I knew now I wasn’t; my body was revealing signs of sickness.

When had climbing a flight of stairs become a challenge?

Why was I losing weight?

Why did I wake up in the morning without the will to start the day?

The cravings of a young man—sexual longings, morning erections, and pleasuring myself in the stillness of the night—these were memories.

Someone my age shouldn’t be dealing with these issues, right?

I am a young man, strong and proud with rugged New England blood, generations of good health, and a life without doctors.

I kept telling myself, ‘Everything is okay.’

I kept repeating, “Everything will be okay.”

But it was never just an irritation in my throat.

The cough wasn’t just spring allergies.

“Hello,” I say.

“You are closer now.”

The wind through an open door has achieved form.

You have become a presence, a physical form I can’t ignore.

“Hello, Jeremiah.”

You’re in the hallway as a guest now, and you’ve even taken off your shoes.

How could I not welcome a guest?

A caller who had been inside, who had been within, was now at my door.

Cradling me as I sit on the shower floor, coughing blood into the drain.

Wrapping me in the steam of a scalding shower that never warms.

You are the fading winter, the arriving spring, and the buds on trees along West Thorndale.

You’re sitting next to me on the L.

The “What-ifs”

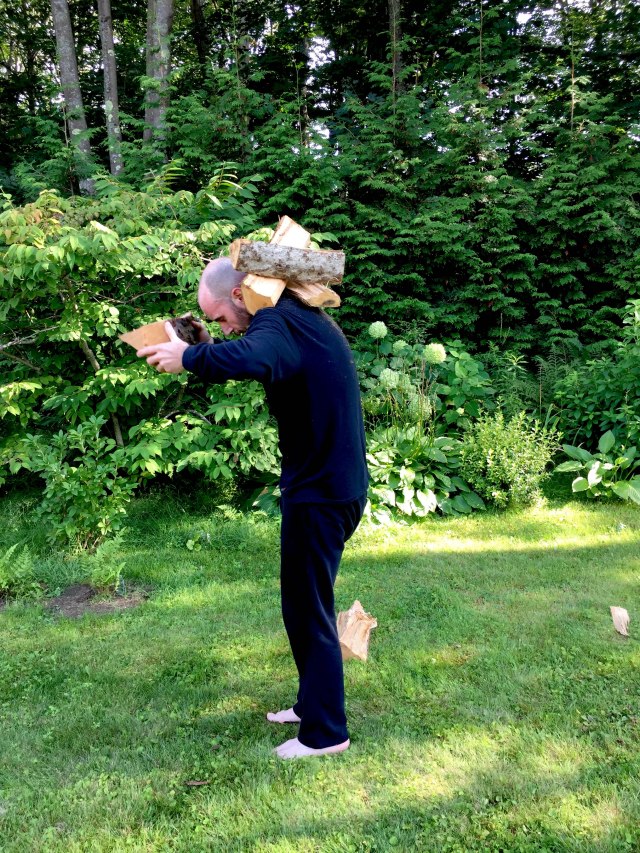

The weight carried,

the what-ifs upon bent backs –

(in) worry and (in) wondering,

“now? if not now, when?”

survivors hold this question;

they live in the moment

of continued burden.

how do I share the weight of gathered

memories?

how do I convey these worries?

I add them singly,

one by one,

layering them,

and bend my back to their weight,

asking,

“if not now, when?”

A Journey

This is a tapestry woven from the insanity and beauty of life. It represents a journey from hopelessness to hopefulness and the process required to move gracefully, albeit clumsily, from one to the other. While there may seem to be no meaning in my cancer diagnosis and the long recovery journey that follows, I am not entirely convinced of this. We find purpose in the absurdity of life’s events and define our mission through the time we are given and the choices we make along the way. I was diagnosed with advanced testicular cancer in April 2016, and I am currently on a path of recovery and healing—a journey of self-love and self-exploration.

Since my cancer diagnosis in 2016, I have been trying to write a memoir about my experience. However, I have found it challenging to make progress, whether because of the emotional triggers this project evokes or its overwhelming scope. Despite these challenges, I have managed to fill numerous journal pages of varying lengths, exploring topics such as illness, mortality, and personal growth.

These are my journal entries posted here in a blog-like format. They consist of rambling thoughts and reflections. I’ve realized that it’s not possible to start at a specific point, such as the date of my diagnosis, and simply move forward, hoping to understand everything. I had to explore a significant portion of my personal history, engaging in self-inquiry and analysis to truly understand the healing process. Healing itself doesn’t begin at one single point. It is a journey.

Although these posts have a sense of linearity, it might be hard to notice at first. Viewing each entry as an individual event, rather than part of a larger story, will provide more insight into my journey. As the story unfolds, it becomes increasingly clear how my life, physical and mental health, and spiritual growth have evolved.

Threads

My sister purchased sweatpants and a cozy sweatshirt for me during the first few weeks of my initial treatment in mid-April 2016. Initially, I didn’t want to wear them to treatment; I wanted to attend each grueling session dressed in a button-down collared shirt and trousers that blurred the line between dress and casual. I liked to look presentable—I needed to.

I arrived at the treatment clinic directly from Chicago, where I worked on completing an MFA, actively attended daily classes, wrote my thesis and art history paper, and generated visual work in general. As such, I consciously dressed in a way that, I hoped, exuded professionalism and spoke to my qualities. There was, however, another very conscious act; I wanted to maintain this daily dress code as a ‘fuck you!’ to cancer.

My work week was, in fact, a full-time job; I was in the treatment center Monday through Friday from 8 am to 4:30 pm. I often arrived before my oncologist and was in my chair, books, and laptop set up and ready to power ahead and finish an art history paper while they were still mixing up my toxic chemo cocktail. On one occasion, I heard my oncologist ask my nurse, “What is he doing over there?” she replied, “he’s working.” As I said, it was my full-time job; I was going to dress the part, grind away, and flip the bird to cancer.

But treatment took its toll.

The nurse who at one time informed my oncologist I was working was now mainlining me with Ativan because the 40-hour week was causing such severe panic attacks.

“It’s Friday; we expect you to be like this,” she said.

Was that a carte blanche to unhook my IVs and run screaming from the clinic? Perhaps, but I didn’t have the energy to do so. Instead, I requested a blanket from the warmer, curled up, and cried.

The following week, I began wearing my new sweatpants and sweatshirt.

No one took a second look at my attire. In fact, I received more attention when I showed up for treatment dressed like I was going in for a day as a data analyst than when I appeared in sweatpants, prepped for an 8-hour treatment cycle. The clothing I usually would only sleep in became my new go-to look on most days.

But it was more than a look, obviously, and more than physical comfort, which became increasingly important as the weeks dragged on. The ease of shedding one pair of sweatpants for another can’t be overstated when depleted of all energy sources.

Since 2016, I have worn the same few pairs of sweatpants to bed when lounging around the house and even while walking on the treadmill. After each washing, I am surprised that they remain intact.

Recently, when I visited my sister, she saw the state of my sweatpants and immediately ordered new ones. She’s like that; without hesitation, she will act in a way that might be simple but can change a person’s entire day – usually for a lot longer.

When I returned home from my visit, the package arrived within a day with various items, and yes, including sweatpants.

With their arrival, I knew it was also time to part with the old pairs. I folded them neatly, ceremoniously, as if I were going to lay them to rest somewhere sacred and not put them in the trash as I did. When I returned to my room, I saw the new sweatpants and, though I partly expected this, became incredibly emotional. For undeniable reasons, there is an aspect of sentimentality brought about by years of owning something. However, when a particular thing has wrapped you up, encased you, and held you literally in its fibers during your most vulnerable times, its presence surpasses sentimentality. That, paired with the endless generosity of my sister, made giving up the old apparel and welcoming the new bittersweet.

It is human nature to want the reassurance that something or someone will catch us if we fall; if we stumble, somebody will help us. The unconscious knowledge comforts us on some primordial level, that a hand will reach out and grasp us and that we can let go.

After trying on my new sweatpants, feeling that strange pleasure of fabric that is both too crisp and refreshingly new, I understood that the garments my sister initially gave in 2016 were indeed that hand reaching out. Somewhere between ceremoniously discarding the well-worn apparel and snipping the tags off the new threads, I understood that the tiniest gesture holds the most significant importance.

I had to remain in the car when my sister purchased the first set of various items for me. I was too ill to go into Old Navy. I sat curled up on her car’s front seat, craving the comfort of my bed, the relief an anti-nausea medication would bring. Her return with multiple bags containing an assortment of clothing was her way of offering me comfort; it was one of many, but this particular gift came during the first stages of my treatment when I felt particularly rough.

We arrived home, and though it was several years (and another lifetime) ago, I can remember the comfort of my new sweatshirt. Though I have since parted with the pants, I refuse to leave behind the sweatshirt and all the memories, good and bad, that it conjures up.

Things change you…

When I smell diesel exhaust, I return to a bus station in Cuenca, Ecuador. I am 11, traveling with my mother. We are visiting my uncle, who was studying there at the time.

Whenever I smell diesel fumes, I am there. I can hear the people yelling out the bus’s destinations, some just boys, perhaps the driver’s son. And other voices are clamoring for space in the cacophony, selling everything from chicklets to newspapers.

It was a culture shock to the highest degree. Before going on the trip, I went to get my passport. I had to take the morning off from school. The lady who was processing it asked where I was going. Because I was wearing my school uniform, I said, “I’m going to school.” I thought she meant where I was going after the appointment.

That’s how innocent I was before the trip.

Things change you.

I saw more poverty in a square mile than I could understand and was then led through an open-air meat market. The smell of diesel fumes mixed with the sight of limbs and heads of various animals while still trying to adjust to roughly 8,000’ above sea level made me want to get sick, but I didn’t. At that young age, a strange and unhinged understanding came over me. If I vomited, I would feel guilty because my stomach was full, and some of the children I had seen looked like they hadn’t eaten in days.

Diesel exhaust will never be diesel exhaust; it will be a time machine.

When I see these clouds (attached photo / Facebook “memory” Jan 30, 2017), It isn’t only that I step onto the cold deck and hear the wooden porch boards protesting against the frigid weather, but I hear my oncologist,

“…the lungs.”

The day is frigid. It’s the type of cold that you can taste before you can feel as if Mother Nature wants to give you a sampling of it before the entire course. (Mother Nature doesn’t care about dietary restrictions.) I take this photo casually. It’s a digital world; I can take dozens, but I remember taking only one.

If I had taken dozens, would I have dozens of different memories?

Unlike diesel fumes, there is nothing discernable about these clouds. They are generic, and they are fleeting. They are ephemeral.

“… the lungs.”

I was going in for an early morning MRI and CT set of scans. I was six months post-treatment. These were routine. Routine is normal, is standard, is regular.

I wanted to remain on the deck, to stay and taste the day and watch these clouds shift and morph into… into anything.

“… the lungs.”

Certain clouds are no longer clouds; they are time machines.

Events change you.

A few days after my scans, when I met with my oncologist, he said,

“… the lungs. It looks like one of the nodules has grown.”

That was seven years ago.

Life changes you.

When I smell diesel, I am transported to another world.

When I see clouds like this, I become someone else, a pre-recurrence Jeremiah, a pre-transplant Jeremiah.

I have witnessed many cloud patterns like this since Jan 30, 2017. They constantly shift; some become rich blue, while others become threatening gray.

Their impermanence serves as a constant reminder of the transient nature of things.

I move forward in this place

Over the past few months, various events or things have triggered me.

Some are minuscule, such as a sound or smell that will set off several memories. Others are more significant, a bodily sensation, an ache, cough, or the like that provokes a more powerful emotional/psychological response.

I note these reactions, a tactic I use to help ground myself. From there, I can move forward, understanding more about it (the trigger) and my relationship with it. If I can, witnessing myself is the trick; detecting what is occurring before being consumed.

The milestone of the five-year cancer-free mark is not an exemption from fear and worry. Sometimes they peak at the same level they did while amid treatment – periodically even more so.

Nights are difficult. Anyone who has experienced a tumultuous and life-altering event can attest that this is when the little dark fears emerge from the woodwork.

A few weeks ago, I returned from Samsø, Denmark (see the previous update here or blog post on thiscyclicallife.blog). A small island with under 4,000 inhabitants, nestled snuggly off the Jutland peninsula. Though it has several adorable little towns, the 40-something square mile island is used primarily for agricultural purposes. To say that it is a walkers’ paradise is an understatement.

When I am state-side, I often sit with these “little dark fears” only to a certain point. It wasn’t a bold pursuit or some other brave endeavor that granted me the time and pace to do so on Samsø; it happened as if on its own.

One night, awoken by worries and fears, I dressed, grabbed my raincoat, and walked. It was almost a knee-jerk reaction. As I joked to a few people, the beautiful thing about an island is that you can’t get lost; you ramble through fields and upon well-worn tractor paths, and sooner or later, you’ll encounter the ocean.

Every evening I filled my rucksack with: a rainjacket, another base layer, extra socks, a flashlight, a field recorder, and bread, butter, and honey, just in case. Then, I’d begin walking if I woke in the night, regardless of the time and conditions, to discover that the fears were present.

State-side, if my worries and fears become too great, and my audiobook or music doesn’t cut through the mix, I’ll bust out trusty ol’ Netflix. I didn’t have such distractions there. Though I purchased a Danish SIM card for emergencies, I didn’t carry my phone or bring my pre-downloaded audiobook.

Bringing the field recorder was the best decision. I didn’t intend to record myself, but I’d sit on some slight rise or the beach and try to collect my thoughts and gather my ideas while talking aloud – a practice I began while in school as it helped me work out ideas. My words were wandering much in the way I was rambling physically.

I have a project in mind for the recordings. Though what follows are some excerpts and snippets I pulled that I found revealing.

*

I move forward in this place (of recovery)

A beacon pulling / a signal drawing

Being held – here

I have learned to live with the memory of you [cancer], as one does with something that echoed, a thing that came.

The lights of Aarhus could be another world – a gentle glow (western paling sky). Aarhus could be Boston from here – Mass General could be anywhere. I could be anywhere. I am here.

Birds; two, then three, then 4, and 5 (a dance that says ‘we are together in this; we heal together.’)

I observe the passage of time by the jar of dirt I keep in my closet.

Between September 2015 and December 2015, I worked as a volunteer fieldhand on Samsø, a small Danish island off the Jutland Peninsula. The island was flat and windswept and, due to the waning tourist season, becoming quieter and quieter. The sun set earlier each day; the island was turning in for the winter. In other words, it was an ideal place for an artist seeking solitude and a reprieve from the hecticness of the city from which I had just left.

On the morning before I left to catch the ferry back to the mainland, which would, in turn, take me back to Copenhagen and onward to Chicago, where I would spend my last semester of grad school, I walked out into a barren field and filled a glass jar with dirt. Though I had only spent three months there, the land had become very important to me, nurturing and fulfilling in a way that so few things had been.

I turned from the field, took the ferry back to the mainland, took the train back to Copenhagen, and took various flights back to the US before commencing what was supposed to be my final semester before completing my MFA.

The jar of dirt came with me.

I left Samsø in mid-December 2015 and was diagnosed in early April 2016.

From there, my health story winds through various surreal, horrifying, and alarming circumstances, culminating in two stem cell transplants, the 2nd of which ended in late August 2017. As such, I am fast approaching the 5-year mark of being in remission and cancer-free. Having experienced a recurrence six months AFTER my initial treatment, this is a remarkable milestone.

Five years.

I can’t wrap my mind around it. I can’t process it.

It is shocking to consider all that has come to pass since August 2017. It is beautiful to witness one’s strength and humbling and frightening to be continually reminded of one’s fragility.

But it all doesn’t add up to five years.

I measure time by the jar of dirt in my closet, the container that survived my rapid exodus from Chicago when I scrambled to return home to Maine for treatment. Dazed by the news of my diagnosis, the surgery, the multi-day stay in the hospital, and the concoction of medication in my system, I still made sure to grab the jar of soil off the shelf in my room. So while other things, such as clothing, books, etc., found their way to the dumpster behind my apartment, the jar of earth stayed close at hand.

This is time.

On Samsø, I stopped carrying a phone. Time lost a feeling of importance and urgency. Towards the end of my work-stay, we’d start work when it was barely light and end when dusk was well upon us. I started learning how much can be understood by the land and how the light fell on it. I realized that I was beginning to comprehend the seasonal shifts of the earth, just as I knew the passing of the day by the soil and how my hands and body felt with it.

This is time.

I observe the passage of time by the jar of dirt I keep in my closet. Sometimes I open the lid and inhale the dwindling scent that carries the history of seasons and crops with it. Now and then, I pour a small amount onto my palm and consider how lucky I am to have known time in two drastically different formats; the abstract form that tells the seasons to shift and the crops to grow and the concrete structure that allows me to understand the significance of this five-year anniversary.

Exist. Live.

Every year, on the 1st of April, I mention that this is the anniversary of my diagnosis. I talk about the irony of it, being that I was diagnosed on April Fool’s Day. (If you can’t see the incongruous nature of that situation, I’m not sure you’ll make it through life unscathed, my dear.) Today, however, I was thinking about other things, things beyond the absurdity of it all, which, to my pleasant surprise, brought about a giggle or two and not “what the fuck?” moments. You see, life is linear, in a roundabout way. Are you with me? I’ll try not to lose either of us, as I clarify.

We can wake up and go to bed and, in between, either exist or live. I was thinking about this as I stood on a small chunk of land poking out into the Bay of Biscay. Far out, somewhere, a storm was rolling and lurching – as they do. I arrived on foot, having walked from Santander. I knew a storm would come; storms always come; they’re linear – in a roundabout way. I didn’t consider the lightning storm. I was not expecting the hail nor the rapid drop in temperature after that. I thought that I had planned for things… We’re always looking, plotting, and considering ways to plan things. Yes, we’re always planning how to prepare. Things. Things. The linearity, the trajectory. Things. I wanted something to go accordingly. I wanted to exist, plan for hail, and prepare for post-graduate life. Things. Bring my gloves for the drop in temperature, and consider how to outline my resume to make a potential employer go, “He’s our guy!”

Existing. It’s existing.

To exist –

verb (used without object)

to have actual being; be:

The world exists, whether you like it or not.

This isn’t a survival story. Nope. I was freezing to death; I wasn’t lost in the depths of the wilderness. This is about sitting under a tree, stuffing my hands into my armpits to keep them warm while watching a storm pass over a gorgeous seascape. I was existing. I was waiting for linearity to run its course. Yep, I’m just sitting there and waiting it out. Linear. Point A – point B

Cancer and cancer survivorship is not linear. You can stuff your pack with all the shit you can think of, and something will come up, and what was once progression is kicked back to point A. It’s linearity in a roundabout way because it’s progression until it’s not. It’s growth until it’s not. It’s freedom until it’s not.

What truly breaks the cycle is opting to live and not simply exist, being and not endlessly planning to be, enjoying being rather than planning on it. I only realized this…today. However, I don’t know exactly. Sometime between waking up and knowing it was my diagnosis anniversary and accepting the fact that I was actually going to stuff my hands into my armpits because my gloves were sitting on the table at my Airbnb.

To live –

Verb (used without object), lived [livd], liv·ing.

To have life, as an organism; be alive; be capable of vital functions:

All things that live.

Falling in love with yourself again is a continuously evolving relationship that will always be fulfilling

As a cancer survivor, it takes time to love the body you felt betrayed you.

Then, however, you begin to see how hard it worked to save you.

Falling in love with yourself again is a continuously evolving relationship that will always be fulfilling!