i waited for you in the park.

when you arrived,

you held me,

and your cold nose pressed against my neck.

you nuzzled me,

and our skin quickly

adapted to one another;

mine cooled, or yours warmed

i’m not sure.

i was happy and

excited about what we might become.

the sun and an early spring day

marked the passage of time

and life moving forward.

these were early days—before

waiting became an annoyance,

before illness,

when i didn’t understand what

holding my breath truly meant.

the anticipation of test results slowed time,

and hours in the treatment chair

felt like lifetimes.

after my first seizure,

when the illness forced my world apart,

time shifted.

you found me

coming to the emergency room

to gather the pieces.

fresh from outdoors,

from the chill of an early

chicago spring day,

remembering this:

your cold nose

pressing into my neck,

i can still feel it as time slowed.

and why can’t these moments

be eternity?

when two bodies

seek a common temperature,

can’t this search last forever?

Tag: testicular cancer awareness

The wind through an open door

At night, lying on my back, I stay awake and listen to the rattling of my lungs.

A wheeze, a strange resonating noise—like damp leaves—if mold had a sound, if abandoned rooms with winds spoke.

I insist I am okay.

I’ve always said, “I’m okay.”

From my youth, my father’s glare, to now, the groan of my lungs.

But I knew now I wasn’t; my body was revealing signs of sickness.

When had climbing a flight of stairs become a challenge?

Why was I losing weight?

Why did I wake up in the morning without the will to start the day?

The cravings of a young man—sexual longings, morning erections, and pleasuring myself in the stillness of the night—these were memories.

Someone my age shouldn’t be dealing with these issues, right?

I am a young man, strong and proud with rugged New England blood, generations of good health, and a life without doctors.

I kept telling myself, ‘Everything is okay.’

I kept repeating, “Everything will be okay.”

But it was never just an irritation in my throat.

The cough wasn’t just spring allergies.

“Hello,” I say.

“You are closer now.”

The wind through an open door has achieved form.

You have become a presence, a physical form I can’t ignore.

“Hello, Jeremiah.”

You’re in the hallway as a guest now, and you’ve even taken off your shoes.

How could I not welcome a guest?

A caller who had been inside, who had been within, was now at my door.

Cradling me as I sit on the shower floor, coughing blood into the drain.

Wrapping me in the steam of a scalding shower that never warms.

You are the fading winter, the arriving spring, and the buds on trees along West Thorndale.

You’re sitting next to me on the L.

The “What-ifs”

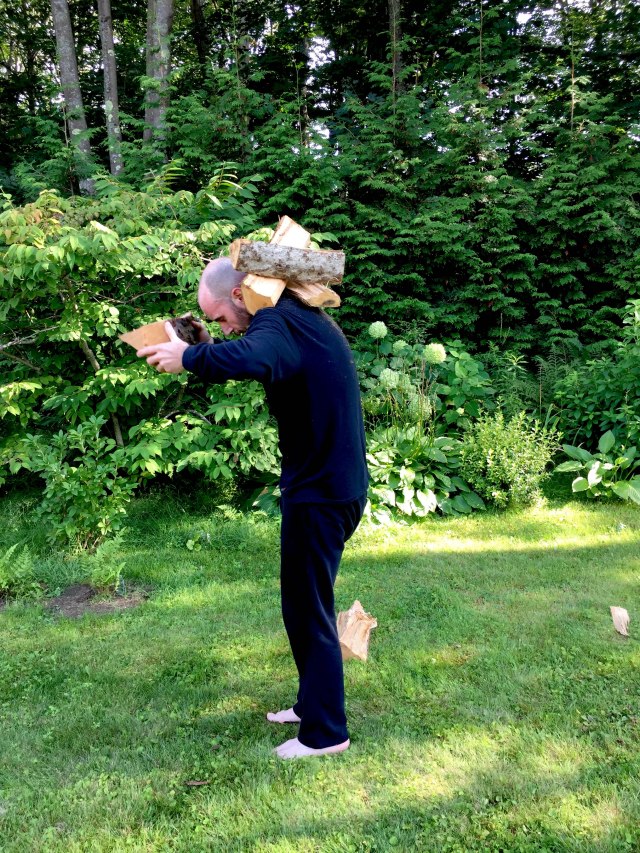

The weight carried,

the what-ifs upon bent backs –

(in) worry and (in) wondering,

“now? if not now, when?”

survivors hold this question;

they live in the moment

of continued burden.

how do I share the weight of gathered

memories?

how do I convey these worries?

I add them singly,

one by one,

layering them,

and bend my back to their weight,

asking,

“if not now, when?”

Medical Alert ID

One of my biggest fears now, and since my diagnosis, is having a seizure. Obviously, I don’t want to have one anywhere/anytime, but my fear is that of having a seizure in public.

The vulnerability I feel when in the post-seizure state (“postictal”) is horrific. I don’t know where I am, who I am, who the people are around me, etc. Once, after a particularly intense seizure, both my mother and sister were sitting on my bed. Luckily, I was in bed at the time, so I didn’t hurt myself after losing consciousness. I frightened my sister so much and undoubtedly saddened her as well because, for the longest time, I just stared at her, unable to recall who she was.

A lot of the trauma I am currently working through with the help of my psychologist is the initial seizure. Currently, I can feel a seizure coming on. There are indications I’ve learned to recognize, often referred to as auras; these help me to take precautions so as not to fall and injure myself. In Chicago, when the first seizure occurred, I had no idea what was happening. I simply hit the deck. When I awoke, I could feel a rocking sensation and the hum and vibration of what I had come to understand as an engine. This knowledge didn’t help, as I had no sense of identity.

The paramedics had rummaged through my belongings and found my ID. This helped them understand who I was, but when they said “Mr. Ray,” I was unsure who or what they were referring to. “Mr. Ray, have you been doing drugs?” They asked this question repeatedly. I struggled, as I often do when regaining consciousness, and since they had no idea if I was, in fact, on drugs, they had me strapped down to the ambulance stretcher. Later, when in the ER, I discovered the cuts on my wrists from having struggled so much while in transport to the hospital. Again, they asked, “Mr. Ray, have you been doing drugs today?” I began to cry. “Mr. Ray, do you know what year it is?” I mumbled something, but I was unsure of what year it was. When I began to come around and gain a greater sense of who I was and where I was, I told them I was a graduate student studying in Chicago. I am sure the latter was evident in Chicago, but this helped them understand more. Finally, one of the paramedics said, “Ok, Mr. Ray, we’re going to untie your arms, ok?” Sometime later, well after I was in The ER, one of the paramedics came to see me. I didn’t recognize him, obviously. “Hi. Mr. Ray,” he said. I am sure he had found out, after inquiring about my toxicology report, that the only drug in my system was caffeine.

I currently wear a medical ID. This simply states that I suffer from grand mal seizures. This isn’t enough for me; I want it obvious that my medical condition is such that I was a cancer patient, and one of the ongoing ailments, perhaps an ailment for the remainder of my life, is seizures.

… I purchased the credit card-sized ID badge and a lanyard. As I gain more emotional and psychological confidence and the much-needed physical stamina, I hope to continue my walking routine, an oft-daily event that I greatly miss, which helps me process much of the events that have occurred over the past few years. I want the ID to be so evident that, should I have a seizure when out and about, my medical condition will be event, glaringly so. I have faith in my fellow man/womxn that, in such an event, I will be comforted and cared for until I regain a sense of who I am…

The thought of waking without knowing who I am, or even what I am, haunts me. The fear of being strapped down during this postictal time is even more so. The vulnerability, as mentioned, is so great that this prevents me from my outings — any outings, be they a trip to a cafe, to take in a movie, etc. I don’t want this fear to become so great that I avoid leaving the house. Currently, I can see this is where my fear and the ever-growing feeling of vulnerability are leading me.

The aluminum, bright red ID card, which I’ll wear around my neck on the outside of my clothing, will hopefully let me inch out more and more and break this paralyzing fear encroaching upon my life.

“Living one day at a time…”

I have had quite a few appointments in the last couple of weeks. I met with my oncologist, and we spoke about the recent MRI. The swelling of the initial lesion in my brain is still stable! As with before, stability is good — excellent! We’ve scheduled another MRI for two months out (mid/late February). With this continued stability, it is unlikely to swell, or continue to swell, more. Though, I am not entirely sure.

I also had a meeting with my neurologist. This was more revealing than the MRI results. As you recall, I wore the ambulatory EEG for 72 hours. All the diodes on my head were connected to a small box I wore around my waist. If any “strange” sensations or feelings arose, I was to press a tiny button on the side of the box. On the EEG reading, this will simply make a note of a specific time, and then, when the neurologist goes over the entire reading, they can go directly to these points and “see” what sort of brain activity was occurring at these specific times.

I pressed the button a total of 33 times over 72 hours. If, for example, I felt slightly dizzy or even disoriented, I pressed the button. I often have these moments when the world seems very distant, or I seem removed from the world. This is very, very difficult to explain. I have tried to articulate it several times. I have taken a step back and am watching the world — an “out of body” experience. This sensation has been so unnerving in the past that I have gone to the emergency room several times.

I was curious how these moments (the “out of body” sensations) would appear on the EEG reading. I was sure that these were some sort of petit mal seizure activity. According to the epilepsy foundation, petit mal seizures, an older term for “absence seizure”, are a type of seizure that causes a sort of lapse in awareness. “Absence seizures usually affect only a person’s awareness of what is happening at that time, with immediate recovery… The person suddenly stops all activity. It may look like he or she is staring off into space or just has a blank look.” This, more or less, sums up the feelings and sensations wherein I am removed from the world, that “out of body” sensation. When I wore the ambulatory EEG (72 hours), I experienced several of these occurrences.

However, nothing on the EEG reading indicated any abnormal brain activity. For 72 hours, everything appeared as it should. Granted, over these 72 hours, there was no reduction of anticonvulsant medication or any other means that, during an inpatient stay for monitoring, a seizure would be provoked. Nonetheless, during these times of “unnerving” sensations (again, the “out of body” experience), nothing out of the ordinary appeared.

This came as a total shock to me. I explained these strange feelings to my neurologist, as I have done in the past, but he again confirmed the results of the ambulatory EEG reading — a reading reviewed by several doctors.

This being the case, he wants to hold off on the inpatient stay for monitoring. “Let’s leave ‘well enough alone,’ Jeremiah.” Again, I pressed him, trying to find answers. I wanted him to pinpoint the reason behind these sensations and explain what was going on within me in plain and simple terms. “… anxiety, most likely, stress, PTSD… a sort of ‘depersonalization'”. This is also the theory of depersonalization that my psychologist holds.

These terms seem so vague. I was expecting to go to my appointment and hear that reading was indicative of these factors; an inpatient stay for monitoring was next in line, and then, after confirmation of particular, definitive activity, brain surgery would follow. My oncologist assured me I didn’t want brain surgery, as does my neurologist. In fact, my neurologist stated rather bluntly that I was to “leave the brain alone!” I insisted that brain surgery wasn’t frightening or an issue as I’ve already had it once. Due to my lack of any formal medical training, my pleas went unheard.

I understand why. Of course, who wants to tamper with the brain — especially this left frontal lobe area where the former lesion is located? When a neurologist and neurosurgeon insist that surgery isn’t an option or an option they are very reluctant to consider, who am I to offer an argument?

It isn’t so much that I want to be seizure-free, though that would be ideal; it is that I want answers. I want to know why; why this and why that. The seizures are just one thing I can fixate on when the larger question is, “Why did any of this happen in the first place?” I want to know why! Why can’t one of these doctors give me a solid answer with all their (western) medical knowledge and years of experience?

I am learning acceptance. I have come a long way in letting go and embracing the unknown over these years. On certain days, today, for example, I can sit with tea in hand and watch the sun slowly migrate across the wall, and there is this peace here.

American theologian Reinhold Niebuhr wrote a sermon concerning this. Though it is best known for its initial/opening lines, it is the second part that, upon rereading it, really strikes a chord with me.

“Living one day at a time,

Enjoying one moment at a time,

Accepting hardship as a pathway to peace…”

I am desperately seeking reasons for this hardship. In doing so, I fear this endless pursuit will overshadow life’s most straightforward, profound, and poetic aspects.

Today, as mentioned, with tea in hand and watching the sun gain its strength each day, I am okay with it — with everything.

A Return

I ventured to the woods the other day. These were the woods wherein my seizure occurred last March.

My mother waited in the car. I had to go alone. I needed the time to be there, process, and allow whatever might arrive.

The season had changed since my last visit. The snowmelt was no longer pooling here and there along the trail, and neither was the chilly bite in the air that remained for some time, even after spring’s arrival. The summer passed without a visit, and I was too frightened to be in the woods — particularly these woods. I was worried a panic attack might trigger a seizure.

When last there, the trees held tiny buds awaiting the perfect, though often invisible, moment to arrive. They had blossomed and were beginning to turn, on the verge of exploding with such vibrant colors as they do so beautifully here in autumn months in New England. Had it indeed been so many months since I was here?

I felt annoyed that the seasons had passed so quickly, but more so that fear had prevented me from returning here — to MY woods. The day was overcast, and I thought it might rain. I was alone with just my thoughts and memories.

After maybe a ½ mile, I rounded the bend in the path and came upon the place where my seizure occurred. Before this, when I walked in, I tried to stroll and be calm, though I could tell my heart rate was increasing steadily; a thin layer of sweat sprouted on my forehead even on this relatively cool day. I nearly turned around and headed back to the car, to the safety it represented, to my mother, and to the security she conveyed.

Ever-present change is more evident in the woods than most anywhere. This may be why I love the woods; perhaps this is why I am in love with the woods. In March, when I last visited them, they exposed themselves openly. The barely present buds left them almost entirely bare, letting the eyes easily pass through the thickets, thin conifers hoping to grow as tall as their brethren, and a few deciduous trees here and there that seemed out of place. Then, in March, just off the footpath, the untrodden snow still lingered, allowing the shadows of the trees to fall upon the ground, shifting with the daylight. These skeletal structures made them appear even more vulnerable. Soon, they will again return to this place of nakedness, letting their leaves blush and climax in such a way I oft wonder if one is worthy enough to witness it. The autumn rains, winds, or the process of the seasons will again reveal the depths into which one can peer… if one is so inclined.

I have not let the woods teach me anything. Instead, I let them teach me everything and then discarded this knowledge. I’m too damn stubborn to accept the reality and pure honesty of it; Nothing. Remains. Constant. Everything. Changes.

It took me several months to return to the woods, to MY woods. I almost forgot their ability to adjust so quickly to change and what message this might hold for me should I be a willing pupil ready to accept the wisdom I desperately seek. I held onto everything cancer had taken away from me; I roped in everything I could think of, from my first seizure in Chicago to the most recent setback, and said, “This is why I can’t return to you!” The woods seemed like the most logical entity I could blame; after all, who else could I point the finger at?

The woods graciously accepted my anger and sadness, my bitterness and tears. They held no hard feelings. When I walked into them and found the location of my seizure, a soft breeze moved through the branches, showing signs of the fast-approaching season. The gentle wind amongst the trees spoke softly, never demanding to know where I had been. Instead, as the wind tossed the branches, they said, “Welcome back, we’ve been waiting for you.”

I lit some sage, pulled the tendrils inward to my being, and then pushed them away to the woods, trying to cleanse something inside me.

PTSD

A few days ago, I decided to check my temperature. I was sniffling, probably due to seasonal allergies, but I was also concerned I might have a cold after taking my temperature, which rested nicely at around 98.6F. I took out an alcohol swab to wipe the end of the thermometer.

Immediately after removing the single-use swab from the packet, the pungent aroma wafted. Shaking almost uncontrollably, I made my way unsteadily to the foot of my bed. There, I continued to tremble, a jittery sensation as though I had consumed too much caffeine. My body warmed, almost a flushing feeling. My knee-jerk reaction in such a situation is to reach for an Ativan.

I was worried I might be too unsteady on my feet, so I chose to remain seated. My reaction, which I now understand to be a “trigger,” was activated by the smell of the alcohol swab. I felt nauseated while sitting on the edge of the bed, but I tried to calm myself by focusing on my breathing and posture. I’ve been practicing this mindfulness technique with the help of my therapist in such situations. Although I have Ativan as a backup, I don’t want to rely on it constantly. I managed to breathe through the intense anxiety, and slowly, it began to dissipate. However, it was followed by extreme fatigue, as usual.

While at Mass General, I had my temp taken regularly, every time vitals were taken. After this, the nurse on duty would wipe the thermometer. It was sterile, just like everything else in my isolated room. So great was the need for precaution that for both my transplants, I saw only the eyes of the nurses, doctors, and visitors as surgical masks shielded their faces. It is tangential, but it does illustrate the necessity for sterility and the regular use of alcohol swabs and other such disposable cleaners.

I have had numerous experiences such as this: legs shaking while at a clinic, nausea during routine blood work, and extreme panic while in an MRI machine. The list goes on and on and on…

I have strayed away from the term “Post Traumatic Stress Disorder,” though I am not sure why. In many ways, I thought it was reserved for people who had experienced events that were far more traumatizing. I also didn’t want to label it, especially that one. I didn’t want to see myself as traumatized. I didn’t want to be in that place. When I was first diagnosed, I hoped to go to the clinic for a few months of treatment and then return to my everyday life. Admitting that I was traumatized would mean needing more treatment, not physical therapy, but rather addressing the ongoing effects of cancer once the initial battle was over.

My psychologist and I have spent numerous hours both addressing aspects of trauma, how it looks and feels, etc., and also skirting the subject altogether. We’ve danced around it, so to speak, but also avoided entirely that which has been glaring at me, lurking, waiting for me to address it and growing larger each day I didn’t.

I thought of trauma as something that held someone back, something that was fixed in a specific time/place. I thought it was an event that never released its talons, rendering someone helpless & forever there, reliving the past events. I didn’t want that. I am embarrassed to admit I thought I was too strong. The idea above, that of strolling into the clinic and strolling back out after a few months, was how I saw myself. After the completion of my second stem cell transplant, and I was a few days away from being discharged, my oncologist said, “Well, you’ve really trooped through these!” That was me, the warrior. I only let my guard down in front of a few select nurses. I held my tears back until I was in the bathroom, supposedly showering; I’d turn on the water and then sit there crying. At night, I would slip into weird, psychedelic dreams, from which I would wake up moaning, curled into a fetal position, clutching my stuffed animal with such force my fingers would ache the next day.

This is fear. This is pain. This is trauma.

I see the label of PTSD as synonymous with being stuck somewhere in the past, reliving it over and over. The truth is, I have barely, if at all, even begun to let myself do that. To relive and work through an event(s) of significant trauma, pain, sadness & anger is, in fact, stronger. When an alcohol swab sends someone into a tailspin, into a place of panic because of the memory it holds, it is evident that something needs to be addressed, something needs to be unpacked.

I have been told that life post-cancer treatment is the most difficult; it is when the real work begins. It is when things rise to the surface and demand to be addressed. If not, they will have their talons firmly fixed into their prey, and one will be held there forever, somewhere in the past.

I’m not going to die…

I’m not going to die, at least not yet.

When my oncologist said, “There is some swelling around the former tumor in your head. This might be the tumor waking up, but we’re not sure right now.”He then mumbled something else, which now escapes my memory, as things do when you’re told such news. Then I mumbled something in response, neither of us wanting to address reality, just mumbling a language that we both agreed upon but neither spoke fluently.

I had several days to mull this over in my mind. It was the longest several days of my life. I played out every possible scenario, walked them all to the end of my imagination, and then started with a new possibility and led that one down the same road. A tumor that had potentially “woken up” and presented with edema (swelling) around it.

Sure, here is the revised text:

I found myself constantly thinking about death. Despite being told that my body could handle more chemotherapy, I questioned whether I really wanted it. After undergoing extensive chemotherapy, did I want to endure more? In addition, I was still dealing with numerous chemotherapy-related issues such as neuropathy, tinnitus, dizzy spells, extreme fatigue, memory problems, slight speech impairment, nightmares, anxiety, and depression. Could I really handle more? Moreover, would additional chemotherapy be effective? Would it only prolong my life without actually curing this disease?

The day before my MRI, I sat on our porch, basking in the beauty of the world around me. The gentle buzz of bees filled the air as they industriously collected pollen from the vibrant flowers. Watching their instinctual knowledge of which blooms were nearing their end was fascinating. I was struck with the realization that we are on a ceaseless quest to evade the inescapable fate of mortality – even more so, the recognition of it.

I truly and honestly looked at death in that glorious sunshine on the porch amidst the bees and butterflies. It wasn’t some philosophical idea, some existentialist pondering, but a cold-hearted fact of what I thought was fast approaching. For the first time since the beginning of all this, since my seizure in Chicago to the most recent comment made by my oncologist about a tumor possibly waking up, I felt okay about it. I felt Okay about the possibility of dying. More importantly, I felt at peace with it.

Even now, writing the words is hard to fully express. Words fall so incredibly short. It is not that I was resigned or apathetic. It wasn’t that death was a welcomed reprieve from the madness of my life that, when it finally arrived, I would ask, “What the fuck took you so long?” It’s that death, the possibility of dying, the likelihood that it would arrive soon, graced me with a profound inner peace, one that I have never before felt in my life.

I didn’t want to move. I didn’t dare shift my gaze out of fear that this would disrupt the sensation and overall feeling I was currently blessed with.

“Hi Jeremiah, this is Dr. _; it looks like the swelling is due to necrosis, a cellular death that can occur after radiation. We’ll just keep track of it; I’ll schedule you for an 8-week follow-up. I don’t think surgical resection is needed, but I’ll put you in touch with a neurosurgeon, and they can go over that with you.

… and that’s it, necrotic tissue causing swelling.

There is a lot of work to be done now. One year post stem cell transplant allows for little breathing room, but that’s plenty for me — that’s more than enough. The real struggle now is with my mind and heart; the PTSD, anxiety, etc., will just take time and patience and love — self-love especially. The level of peace, however, and the acceptance I felt on that day, and still feel now, will go a long, long way in my emotional & psychological recovery. In using the metaphor of one of my latest posts regarding my feeling of helplessness & exhaustion being like the crashing waves under which I’m struggling to stay afloat, I can touch the sea floor now. Also, the land is clearly visible, and the tide finally works in my favor.

April is testicular cancer awareness month

How I got here. Wherever here is.

I decided to visit the school nurse and ask about the dry cough that had been lingering. There was a sort of clinic located on campus for students. I decided to make an appointment. At this time, the cough was starting to interfere with my daily life; in the morning, after doing my daily pushups, I had to hold my arms above my head to get a lung-full of air.

The nurse practitioner (NP) was a little confused. I was a-symptomatic, except for the cough. When they asked about my health history, I told them I hadn’t been sick a day. They prescribed an albuterol inhaler to see if this would help. It did, but only momentarily. I returned to the clinic, and the NP said I might want to visit a walk-in clinic near the school and see a doctor. So, I did. Again, I’m thinking this is merely a cough due to allergies, maybe I’ve developed asthma, etc. I was a “strapping young man,” and surely it couldn’t be anything more than that.

The Dr. at the clinic was also a little baffled. I had no signs of any illness at all; no fever, swollen glands, nausea/vomiting, etc., and again, no history of ill health. They decided to do an x-ray of my chest, which they could do right there at the clinic. After waiting a considerable amount of time, the Dr. again was a little confused by the x-ray results and wanted something with a more “in-depth” look at my lungs. I was told to schedule a CT scan. Again, I was in school full time, trying to keep up with a considerable course load, getting ready to install my thesis work, working a part-time job, etc. This all seemed like a nuisance. However, I assumed the Dr. would know best, so I scheduled an appointment for a CT scan.

I went to the appointment and was informed that I would have to pay well over a grand ($1,000) for the procedure. I was shocked, naturally. I had very little money, but my insurance deductible was so high that I was paying for the procedure out of pocket. Also, everything was well out of network… which I didn’t understand because I was a “strapping you man” and didn’t ever, ever even use insurance. I basically had it because students must have a plan or buy one from the school. The plan I purchased through the “affordable care” act was a bare-bones plan with a $6,500 deductible. But I bit the bullet and paid for the scan with my credit card,

I left the facility, and even though I just put a “pointless” procedure on my credit card, I was happy as the day was so beautiful. I thought I’d take my habitual long walk and soak in the sun. My cough, though persistent, never prevented me from my daily walk. I needed exercise, and still do, to maintain a clear head, and since my walks have become so routine, I find myself craving them.

The CT scan results would be sent to the ordering physician at the walk-in clinic.

A few days later, the clinic called me and said the Dr. wanted to see me regarding my results. Annoyed again, I left work early and headed to the clinic. I waited long, as it was a walk-in clinic for various ailments and people seeking medical attention. Finally, the Dr. saw me. They said the CT scan was a bit strange and showed my lungs were full of this sort of white, wispy stuff. They said they didn’t want to jump immediately to the idea of it being cancer, but they had a sneaking suspicion it was. They said it wasn’t primary lung cancer, as this would certainly be noticeable, but it could be cancer that had spread to the lungs. I was given a little time to myself in their office as this was “a lot to process.” However, I still assumed it was nothing — I was certain it wasn’t anything to worry about. I was, again, a “strapping young man,” and this was some sort of lung infection or … something else, but not cancer.

The Dr. returned and said I’d need to have a biopsy to determine what it was and, if it was, in fact, cancer, where it originated. They gave me a list of hospitals and local Drs. etc. Told me to contact my insurance about out of network possibilities, etc. Then, with a handshake and a wish for good luck, I was off.

It still didn’t phase me. Trust me, it wasn’t naïvety, I simply didn’t believe that it was cancer of any sorts. On top of that, there was NO way I could have a biopsy done. Though not a complex procedure, it would require time from school, work, etc. Also, now slightly grasping the insanity of the US insurance system, I would have to pay for all, or at least a great portion of the procedure, from my dwindling savings or, again, charge it. If it was an emergent situation (such as after the seizure and being rushed to the hospital). But this wasn’t emergent, not yet, at least. I couldn’t do that; I couldn’t take the time away from school or work. I was so close to graduating, so close to being done. I thought I could just finish up and fly back to New England, once there I could have the biopsy. Yes, that was my plan, and, to me at the time, it made perfect sense. I was only a matter of weeks away from completing my graduate degree and could be back home, back within the network of my insurance plan, and then could have this procedure done. Plus, I was a “strapping you man,” remember, and certainly wasn’t sick — not a single symptom, except for the dry cough.

But I was sick. In fact, I was worse than just sick; it was worse than a dry cough I couldn’t kick. I was told that, in a healthy, young person, cancer can spread far and wide inside the lungs. However, the brain has limited room… about 1.5-2 weeks after I was told I would need a biopsy to understand if this was cancer or not, I had the infamous seizure. The cancer, undoubtedly, was already spreading and had been doing so for months. At the time of my CT scan, there was unquestionably a growing lesion already in my brain.

April is testicular cancer awareness month. A list of symptoms/signs one can have might indicate having it. Be mindful of your body, perform self-examinations at least once a month, etc. — early detection is key. Even “strapping young men” are not invincible or immune.

Birthdays

Birthdays are always an interesting point of reference to look back at time. They make a good starting place to look at a swath of years and note changes, growth, etc., to take one birthday, jump backward to the previous year, and look at the space in between.

On September 18, 2017, I turned 35 years old. Initially, I was not excited about the approaching birthday as the years from 33 ½ to 35 (from diagnosis to present) were lost for lack of a better term. This was my mentality leading up to the day — that that time was irreplaceable, gone, etc.

There are two ways to view this: as time being lost, with those years and months of being sick and in and out of treatment, or as something relative. I wasn’t even sure I would live to see my recent birthday. During the last round of high-dose chemo, when I was at the lowest point imaginable, I asked the night nurse if I was going to die. Feeling as I did, I was sure I wouldn’t live to see the following day, let alone my 35th birthday, which was only a matter of weeks away. Thus, the relativity of age, years, and time.

I awoke on my 35th birthday feeling more positive and ready — I had lived to see the day.

I’ve been trying to avoid dwelling on the past and revisiting the years before my diagnosis. However, I can’t help but remember significant moments, like birthdays, that were not overshadowed by poor health. Time now feels like it’s split into two distinct sections: before and after my diagnosis. But in reality, time doesn’t work that way; life is a mix of moments and events that all come together. Focusing on the present and fully embracing our current moments is essential. While there are events I wish I could erase from my memory, it’s impossible to pick and choose our experiences selectively. Who would we be without these moments, both good and bad? Who would we be without the nights we thought we wouldn’t survive and the mornings that surprised us by arriving?